Healthcare at the edges

defining rural healthcare as a complex, community-driven system

Systems

CARE

Where this all started.

We began this project broadly, knowing we wanted to study healthcare as a system. We were interested in care relationships, access, and how technology reshapes the way people interact with providers. From the start, we knew we would need to narrow—but we didn’t want to decide how too early.

As we moved through secondary research, a pattern became hard to ignore. Rural communities were consistently discussed in terms of lack—lack of access, lack of providers, lack of infrastructure—yet rarely from the perspective of the people living there.

That tension led us to rural healthcare.

Macks and Kaitlyn both brought personal connections to rural America through family, upbringing, and long-term relationships. They carried an intuitive understanding of rural rhythms and values and led much of the project’s visual and illustrative work. I didn’t share that lived connection. What I brought instead was distance—and a responsibility to listen carefully, question assumptions, and help us build shared language rather than project meaning onto participants’ lives.

Designing research for complexity.

Because we were entering a space shaped by strong cultural context, we designed our research to stay open as long as possible.

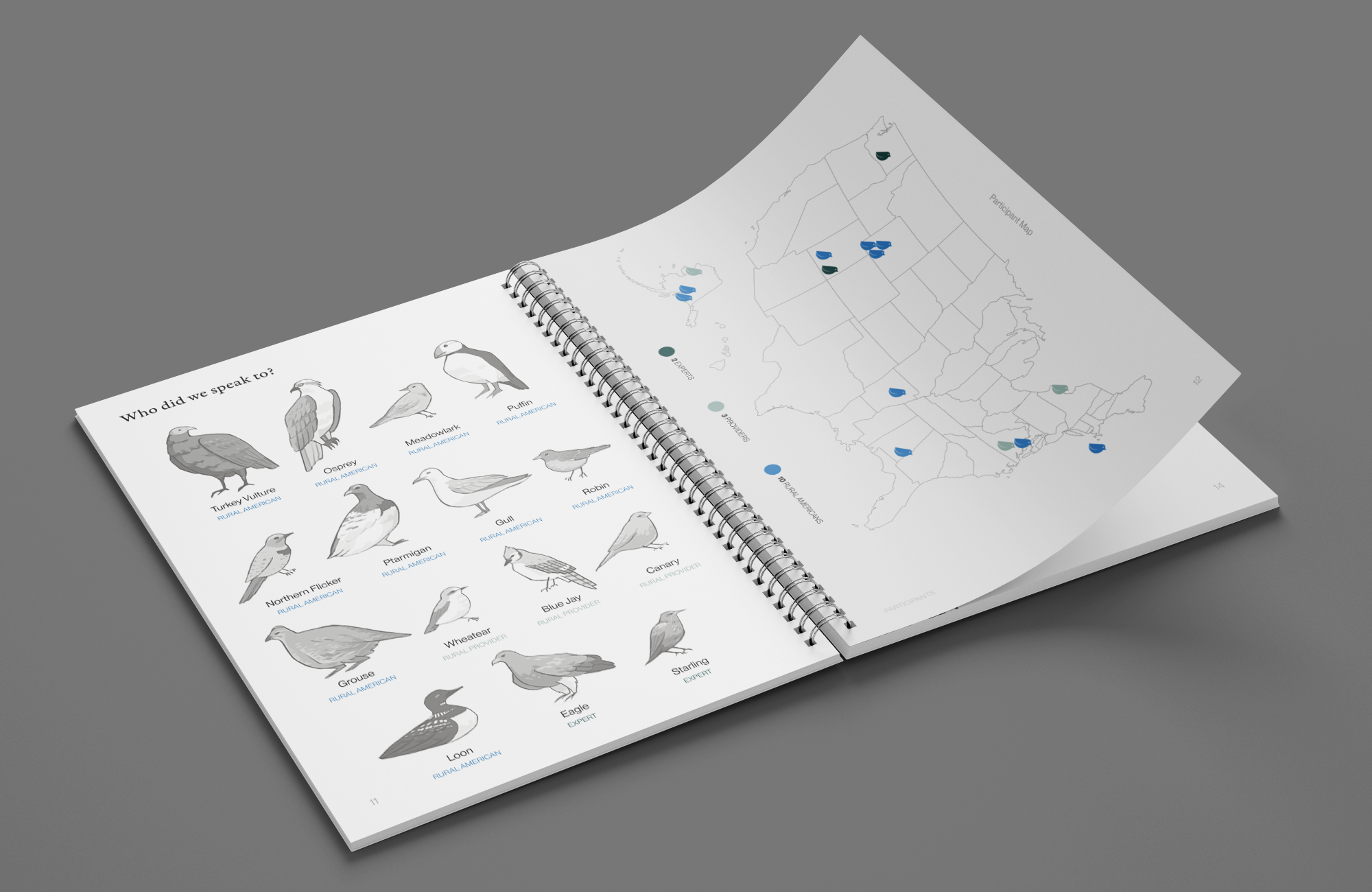

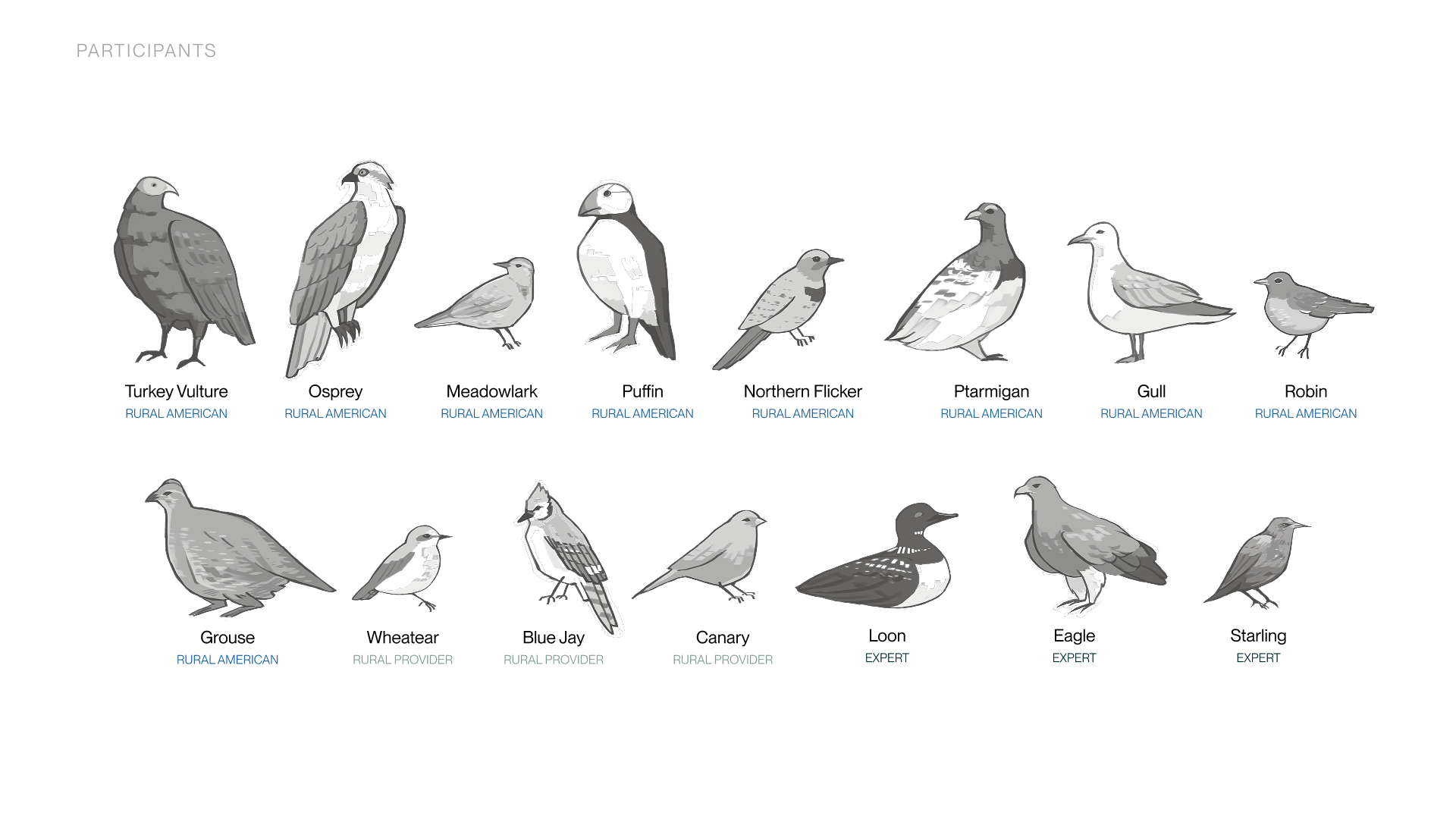

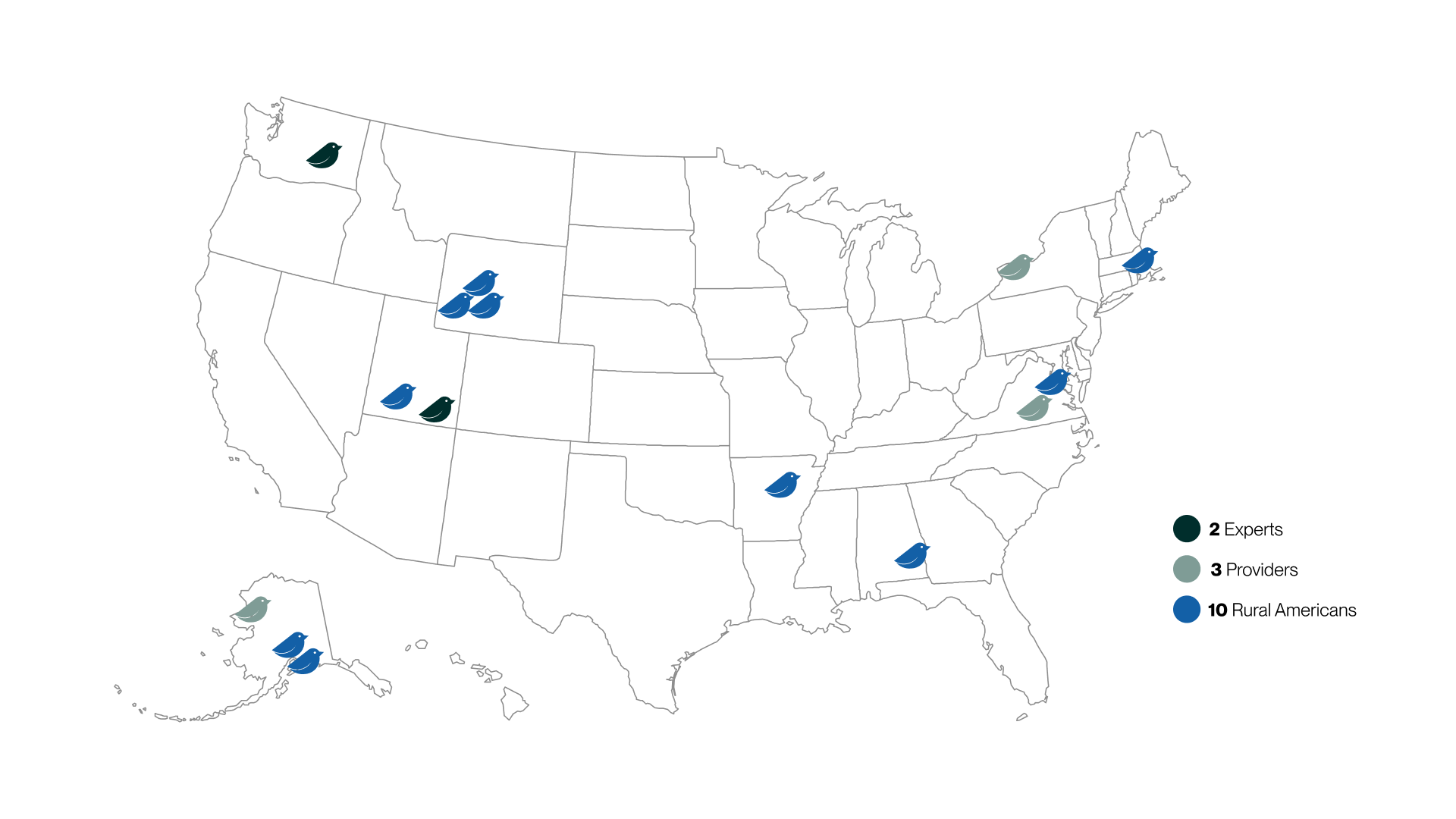

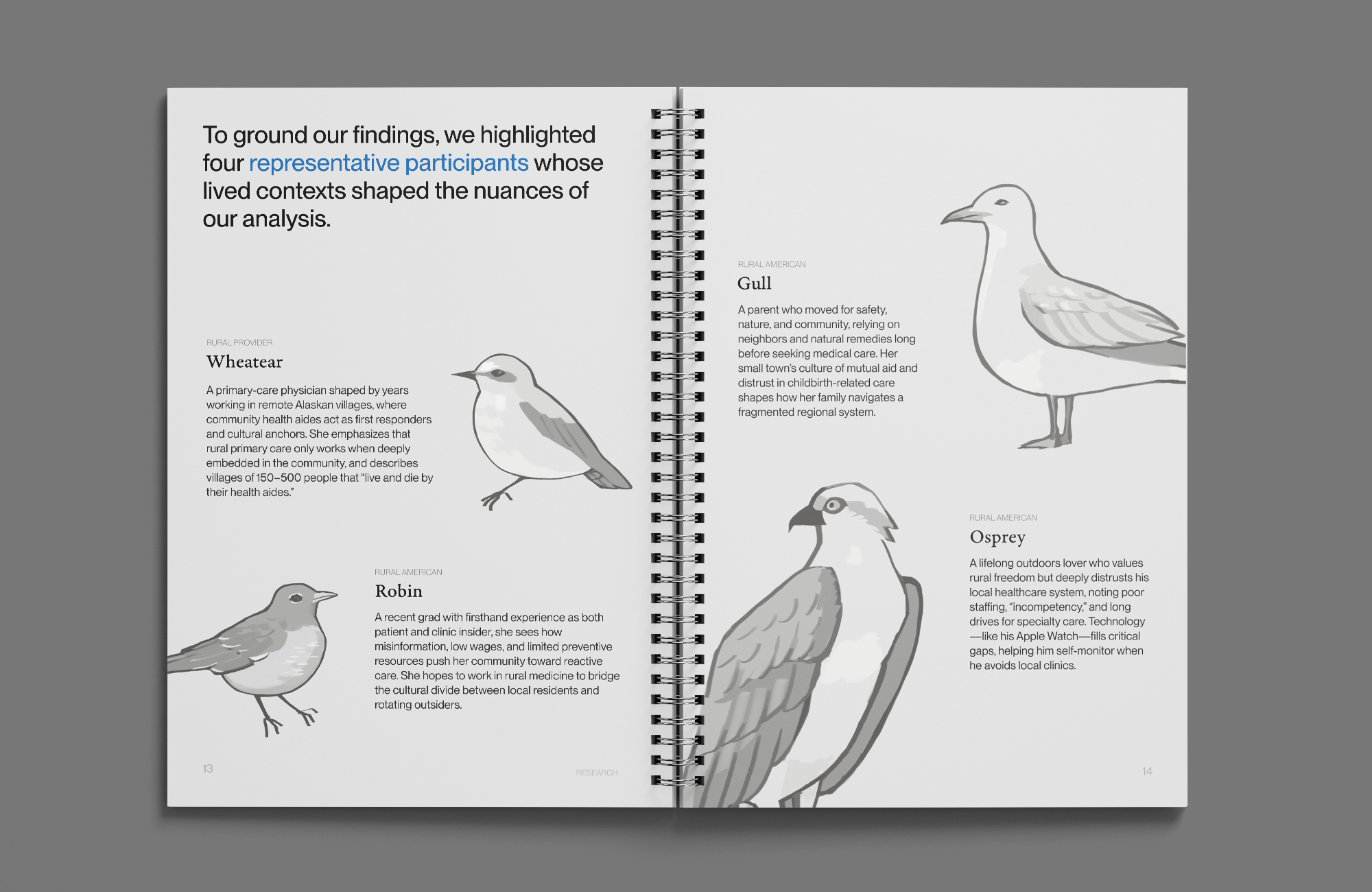

We centered rural Americans—voices often underrepresented in design research—and paired them with rural providers and policy experts to understand care from multiple positions within the system. All research was conducted remotely, which required us to adapt our methods in real time.

Participants completed:

- a photo study documenting their care environments

- directed storytelling prompts

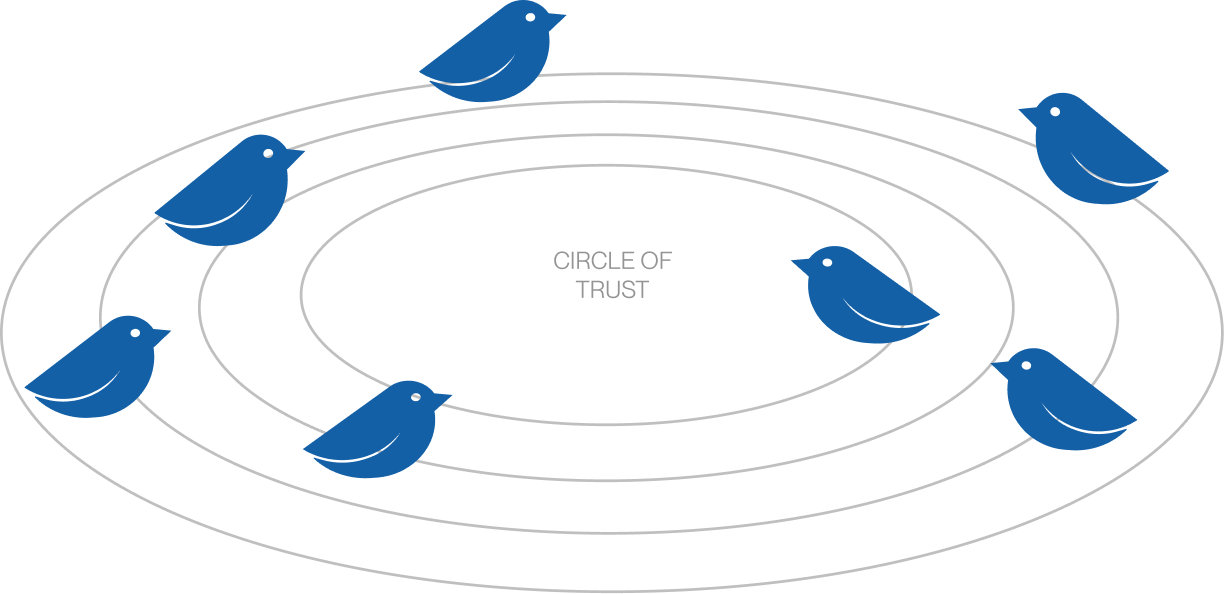

- mapping activities like the Circle of Trust

- and conversational interviews

When photo studies didn’t work, one participant suggested walking us through their town on Google Maps. That shift became a turning point. What began as a workaround became one of our most revealing methods, showing us where care actually happens—and where formal systems fall away.

When the question stopped working.

As we began synthesis, it became clear that our initial research question wasn’t holding the complexity of what we were hearing.

Rural America wasn’t one thing. Alaska didn’t resemble Wyoming. Virginia carried entirely different concerns. Even within the same town, care meant different things depending on family roles, histories, and trust.

We paused and reframed.

Instead of asking how technology could improve rural healthcare, we asked:

How do different cultural realities of rural communities shape how providers and community members understand and practice care?

That reframing allowed us to stop chasing solutions and start understanding systems.

The

Findings

Definition became my contribution.

At that point, my role sharpened around synthesis and definition-making.

I led the work of translating transcripts, maps, and stories into shared language the team could design from. Rather than jumping to insights, I focused on identifying the structures underneath them.

We defined concepts like:

- Scarcity as a baseline condition rather than a failure

- Continuity as long-term presence, often valued over efficiency

- Belonging as a prerequisite for trust

- Interpretation as the way communities reshape external systems

These definitions became the scaffolding for our insights, principles, and speculative work.

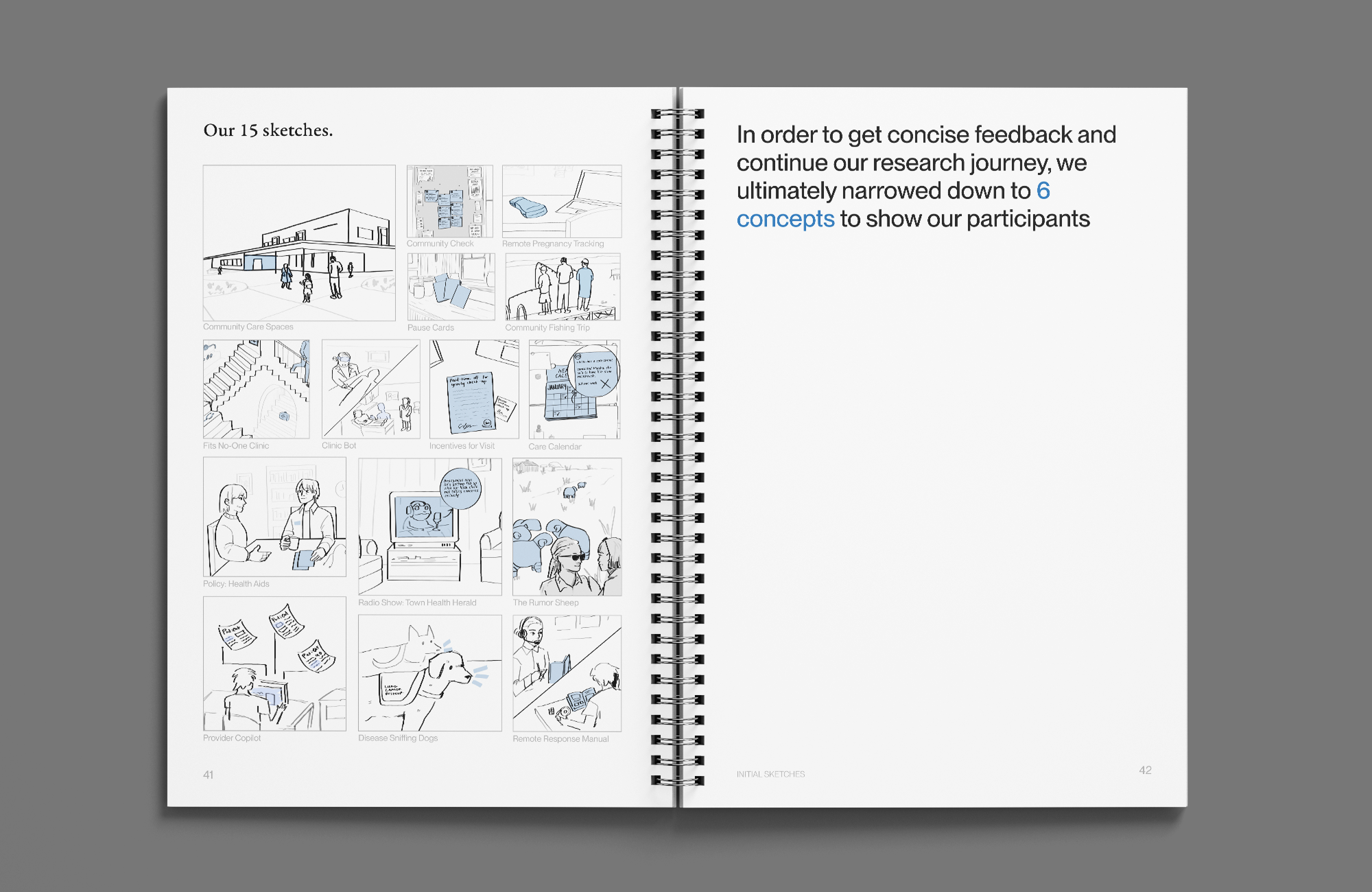

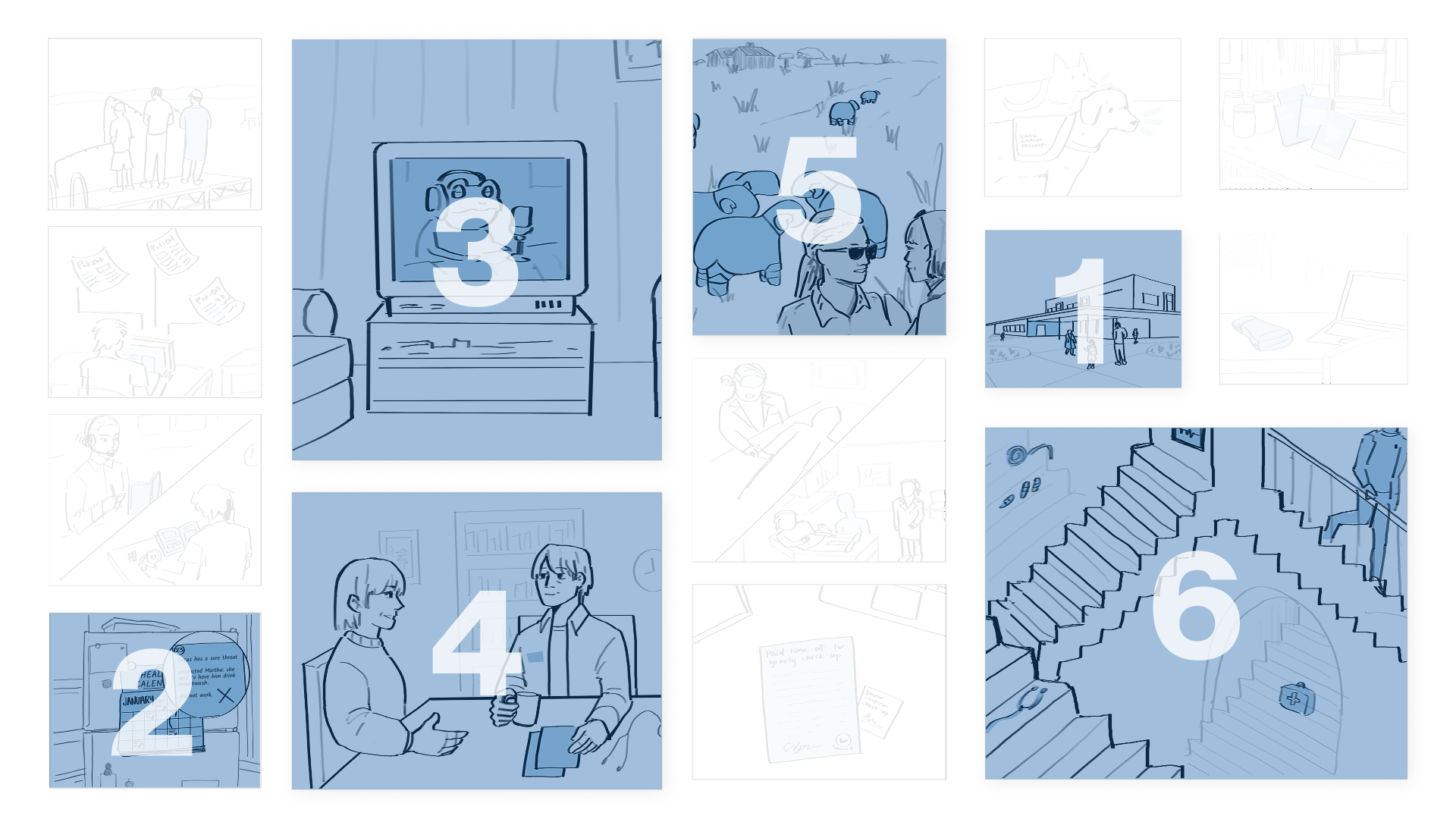

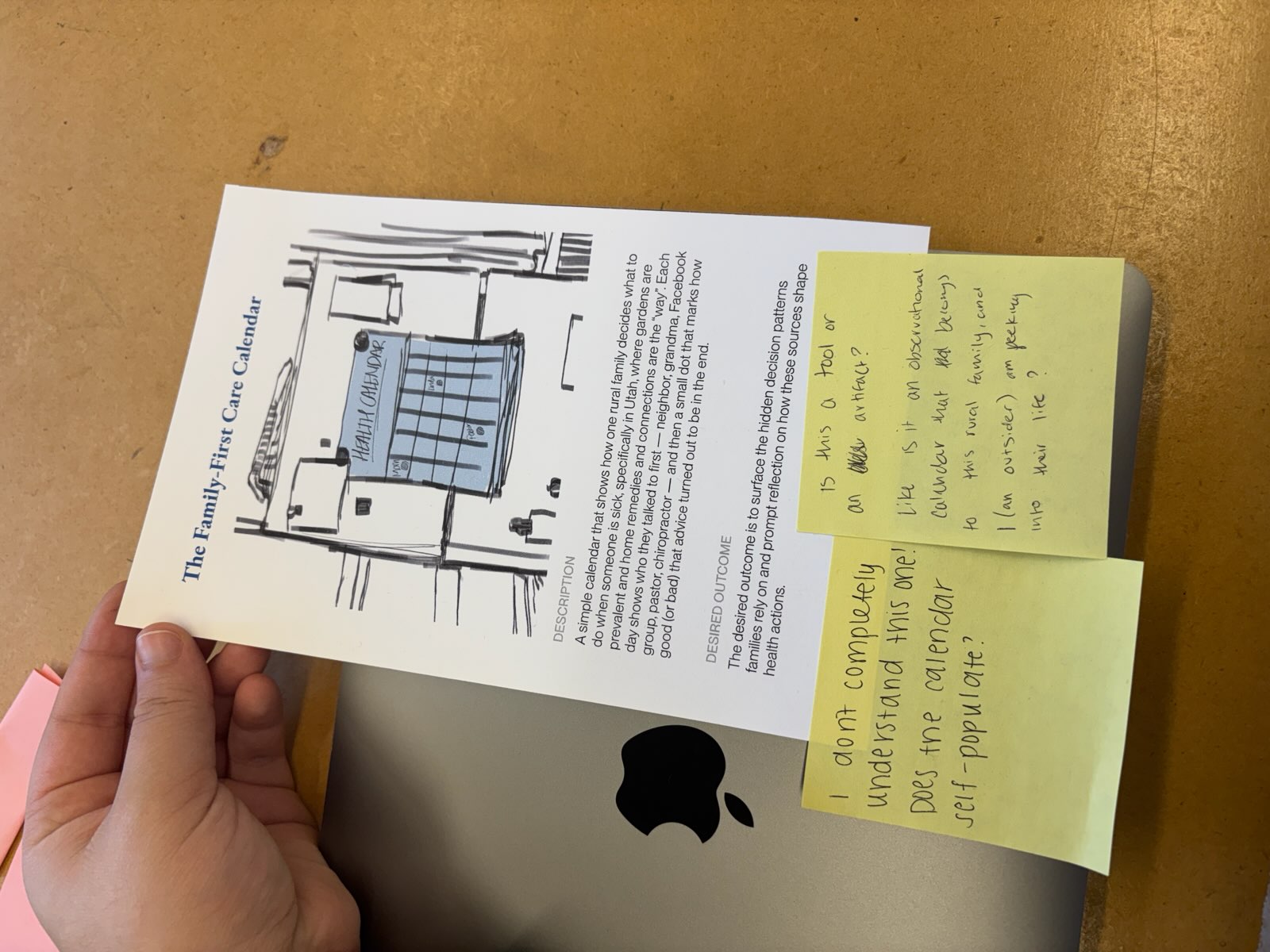

Using speculation to test our understanding.

We split the visual exploration quite evenly, producing a wide range of speculative sketches grounded in rural contexts. Together, we treated these sketches not as solutions, but as research probes.

We narrowed from fifteen concepts to six and returned them to participants. Their feedback both validated and challenged ideas. Participants rewrote concepts, flagged risks, and surfaced tensions we hadn’t fully seen.

That feedback shaped our final findings more than any single sketch.

In rural America, healthcare is not a fixed service relationship, it is a socially embedded relationship that must continuously adapt to the specific community it serves.

Final Thoughts

Rural healthcare is not a single problem to solve, but a network of relationships shaped by history, culture, scarcity, and trust. My primary contribution, and what I'm most proud of, was my work in trying to make that system legible.

I focused on translating our data and stories into shared language the team could design from. This meant recognizing when our original research question wasn’t working, reframing it, and developing clear definitions—such as scarcity, continuity, belonging, and interpretation—that grounded our insights and principles. That definition work shaped every decision that followed, from how we positioned the problem space to how we evaluated speculative concepts.

I also want to foreground how we used speculative sketching as a research tool, not a solution space. The sketches helped us test assumptions, surface tensions, and invite participants to critique our understanding of their care systems. Presenting this project in my portfolio allows me to emphasize how I try to approach research: slowing down, defining carefully, and using design to understand complex systems rather than simplify them too early.